My Approach to Qazaq Music as a Composer

by Werner Linden

First, I need to be haunted by the original piece, it must be fascinating to me musically. When I wish to work on preexisting music, before I work on it, I need the original notes without any alteration. So, if the notes of that original aren’t available to me, I transcribe from the recorded interpretations of the tune.

In oral traditions, such as Qazaq music, it often happens that there are recordings by several performers available. In this case I transcribe them all: not in comparison with each other, but to use them all, So, instead of creating a true repetition of a motif in the piece, I use one of the different available versions [performances] as the motif.

During the transcription process, of course, I have ideas of which second melodies and / or harmonies I could add, and of those ideas, I make notes, so as not to lose them in the process [of arranging].

I also get an impression of the character of the tune I am transcribing, which might result in deciding which instruments will play the main role in my version of the piece. Starting on my score, the first step is to import the transcription of the original, and to assign it to the instruments I find most appropriate. This includes an outline of the piece’s dramaturgy as I perceive it.

Then I return to my notes about secondary melodies and harmonies, which I apply according to that dramaturgical outline that I bear in my mind.

The Structure of Qazaqstanda, 2nd. half

1. Mashina, Qurmanghazy (Машина, Қурманғазы)

2. Shalqyma, Sügir (Шалқыма, Сүгір)

3. Qusni Säulem, E. Qyzyken (Құсни Сәулем, Е. Қызыкен)

4. Montage:

- Kertolghau, Kojeke Söyimbek (Кертолғау, Қожеке Сөйімбек)

- Толғау, Омархан, (Tolghau, Omarxan)

- Shortpanbaydyng Shertpesy Bazaraly, Shortpanbay (Шортанбайдың шертпесі Базаралы, Шортанбай)

5. Kökeykesti Äbiken (Көкейкесті Әбікен)

6. Kökek (Көкек)

7. Kishkentau, Qurmanghazy (Қурманғазы)

8. Altynbek, Raushan Orazbaeva

9. Balbyrauyn, Qurmanghazy (Қурманғазы)

10. Köroghly Murat -Mangystau

So, the piece is growing and it might happen that from the “accompanying material” develops rather intense side motifs which are not linked to the original tune, but they arise from the accompaniment like a counterpoint to the original.

The steps of creating the accompaniment are not a process that goes straight from the beginning to the end. It is constant listening, “adjusting”, to keep the piece flowing, as the original is in a flow, too. This is why, when I create a piece based on traditional music, I do not lay down too many plans which might bind me during the creative process.

But whatever I might add to the original melody, it is important to me that the original always plays the main role; it must be clear to the listener to which tune I am referring.

For Qazaqstanda Pt 2.

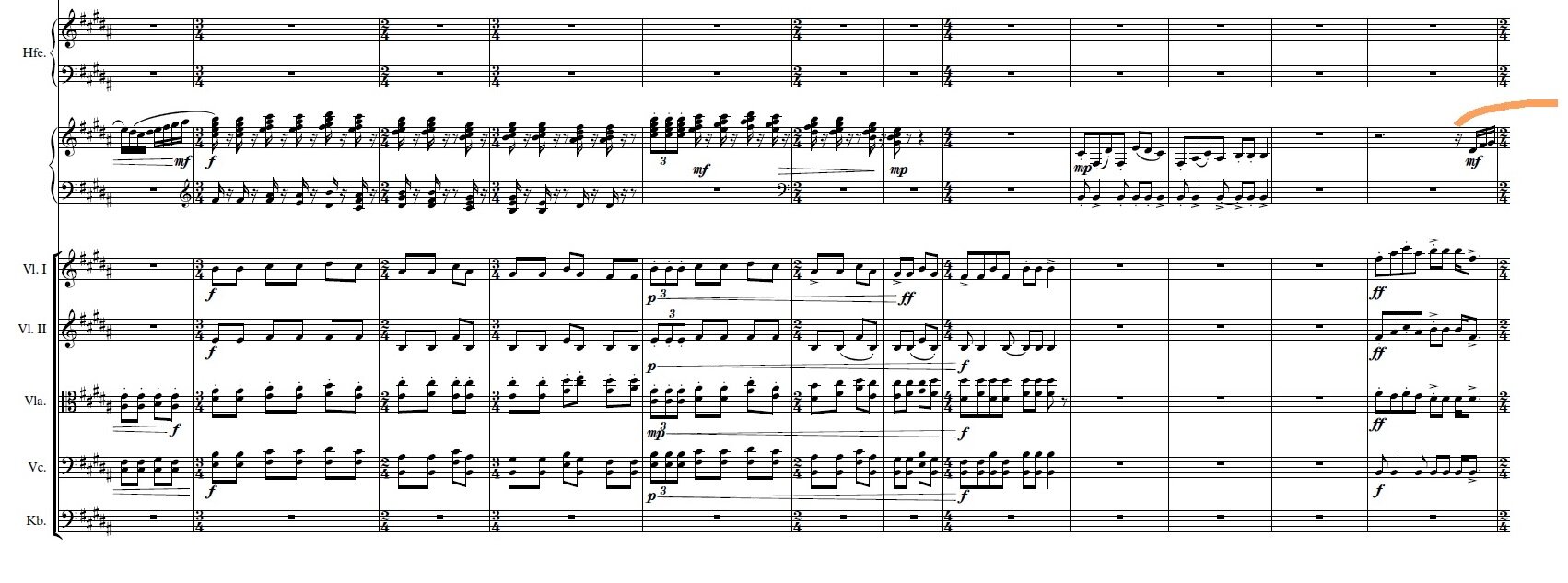

This is taken from “Bozingen.” The yellow marked lines show how I split the original melody and distributed it to the different colors of orchestral instruments. So the original melody goes without interruption, but it changes the timbre.

These two are from Dina Nurpeisova’s “Nauai.” Here you see the strings section with the piano, first they go together, at the end of the first image you see the piano is going off the tune and plays a new thing before it joins the ensemble again.

Other composers might be opposed to my efforts, saying that the era of using folkloristic elements in their own music finished with great composers like Bartók and Stravinsky, and in contemporary music the main essence is diving into the research of sound, even the creation of new instruments in the pursuit of research. My answer to this valid objection is: They are completely right. It is the basic concept of contemporary music that with each piece a composer sets out to create, the first step is a re-valuation of the composer himself, as it was exemplarily done by Pierre Boulez in the middle of the last century, when he composed “Structures”, or by Harry Partch, Luigi Nono, or John Cage.

But I am not saying that, using a traditional source, the resulting work is my work. It isn’t. It is my interpretation of that original tune. When I do such a work it is my aim to create a kind of musical platform in order to help listeners to get acquainted with music they possibly never heard before. My interpretations should serve as a medium to widen the listener’s musical perspective.